Pythagorean theorem

| Trigonometry |

|---|

| History Usage Functions Generalized Inverse functions Further reading |

| Reference |

| Identities Exact constants Trigonometric tables |

| Laws and theorems |

| Law of sines Law of cosines Law of tangents Pythagorean theorem |

| Calculus |

| Trigonometric substitution Integrals of functions Derivatives of functions Integrals of inverse functions |

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a relation in Euclidean geometry among the three sides of a right triangle (right-angled triangle). In terms of areas, it states:

In any right triangle, the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares whose sides are the two legs (the two sides that meet at a right angle).

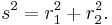

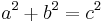

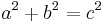

The theorem can be written as an equation relating the lengths of the sides a, b and c, often called the Pythagorean equation:[1]

where c represents the length of the hypotenuse, and a and b represent the lengths of the other two sides.

These two formulations show two fundamental aspects of this theorem: it is both a statement about areas and about lengths. Tobias Dantzig refers to these as areal and metric interpretations.[2][3] Some proofs of the theorem are based on one interpretation, some upon the other. Thus, Pythagoras' theorem stands with one foot in geometry and the other in algebra, a connection made clear originally by Descartes in his work La Géométrie, and extending today into other branches of mathematics.[4]

The Pythagorean theorem has been modified to apply outside its original domain. A number of these generalizations are described below, including extension to many-dimensional Euclidean spaces, to spaces that are not Euclidean, to objects that are not right triangles, and indeed, to objects that are not triangles at all, but n-dimensional solids.

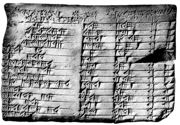

The Pythagorean theorem is named after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who by tradition is credited with its discovery and proof,[5][6] although it is often argued that knowledge of the theorem predates him. (There is much evidence that Babylonian mathematicians understood the formula, although there is little surviving evidence that they fitted it into a mathematical framework.[7]) “[To the Egyptians and Babylonians] mathematics provided practical tools in the form of "recipes" designed for specific calculations. Pythagoras, on the other hand, was one of the first to grasp numbers as abstract entities that exist in their own right.”[8] In addition to a separate section devoted to the history of Pythagoras' theorem, historical asides and sources are found in many of the other subsections.

The Pythagorean theorem has attracted interest outside mathematics as a symbol of mathematical abstruseness, mystique, or intellectual power. The article ends with a section on pop references to the theorem.

Other forms

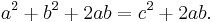

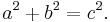

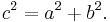

As pointed out in the introduction, if c denotes the length of the hypotenuse and a and b denote the lengths of the other two sides, Pythagoras' theorem can be expressed as the Pythagorean equation:

or, solved for c:

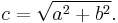

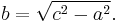

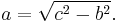

If c is known, and the length of one of the legs must be found, the following equations can be used:

or

The Pythagorean equation provides a simple relation among the three sides of a right triangle so that if the lengths of any two sides are known, the length of the third side can be found. A generalization of this theorem is the law of cosines, which allows the computation of the length of the third side of any triangle, given the lengths of two sides and the size of the angle between them. If the angle between the sides is a right angle, the law of cosines reduces to the Pythagorean equation.

Proofs

This theorem may have more known proofs than any other (the law of quadratic reciprocity being another contender for that distinction); the book The Pythagorean Proposition contains 370 proofs.[9]

Proof using similar triangles

This proof is based on the proportionality of the sides of two similar triangles, that is, upon the fact that the ratio of any two corresponding sides of similar triangles is the same regardless of the size of the triangles.

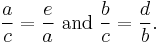

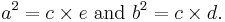

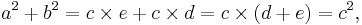

Let ABC represent a right triangle, with the right angle located at C, as shown on the figure. We draw the altitude from point C, and call H its intersection with the side AB. Point H divides the length of the hypotenuse c into parts d and e. The new triangle ACH is similar to triangle ABC, because they both have a right angle (by definition of the altitude), and they share the angle at A, meaning that the third angle will be the same in both triangles as well, marked as θ in the figure. By a similar reasoning, the triangle CBH is also similar to ABC. The proof of similarity of the triangles requires the Triangle postulate: the sum of the angles in a triangle is two right angles, and is equivalent to the parallel postulate. Similarity of the triangles leads to the equality of ratios of corresponding sides:

The first result equates the cosine of each angle θ and the second result equates the sines.

These ratios can be written as:

Summing these two equalities, we obtain

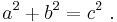

which, tidying up, is the Pythagorean theorem:

This is a metric proof in the sense of Dantzig, one that depends on lengths, not areas. The role of this proof in history is the subject of much speculation. The underlying question is why Euclid did not use this proof, but invented another. One conjecture is that the proof by similar triangles involved a theory of proportions, a topic not discussed until later in the Elements, and that the theory of proportions needed further development at that time.[10][11]

Euclid's proof

In outline, here is how the proof in Euclid's Elements proceeds. The large square is divided into a left and right rectangle. A triangle is constructed that has half the area of the left rectangle. Then another triangle is constructed that has half the area of the square on the left-most side. These two triangles are shown to be congruent, proving this square has the same area as the left rectangle. This argument is followed by a similar version for the right rectangle and the remaining square. Putting the two rectangles together to reform the square on the hypotenuse, its area is the same as the sum of the area of the other two squares. The details are next.

Let A, B, C be the vertices of a right triangle, with a right angle at A. Drop a perpendicular from A to the side opposite the hypotenuse in the square on the hypotenuse. That line divides the square on the hypotenuse into two rectangles, each having the same area as one of the two squares on the legs.

For the formal proof, we require four elementary lemmata:

- If two triangles have two sides of the one equal to two sides of the other, each to each, and the angles included by those sides equal, then the triangles are congruent (side-angle-side).

- The area of a triangle is half the area of any parallelogram on the same base and having the same altitude.

- The area of a rectangle is equal to the product of two adjacent sides.

- The area of a square is equal to the product of two of its sides (follows from 3).

Next, each top square is related to a triangle congruent with another triangle related in turn to one of two rectangles making up the lower square.[12]

The proof is as follows:

- Let ACB be a right-angled triangle with right angle CAB.

- On each of the sides BC, AB, and CA, squares are drawn, CBDE, BAGF, and ACIH, in that order. The construction of squares requires the immediately preceding theorems in Euclid, and depends upon the parallel postulate.[13]

- From A, draw a line parallel to BD and CE. It will perpendicularly intersect BC and DE at K and L, respectively.

- Join CF and AD, to form the triangles BCF and BDA.

- Angles CAB and BAG are both right angles; therefore C, A, and G are collinear. Similarly for B, A, and H.

- Angles CBD and FBA are both right angles; therefore angle ABD equals angle FBC, since both are the sum of a right angle and angle ABC.

- Since AB and BD are equal to FB and BC, respectively, triangle ABD must be congruent to triangle FBC.

- Since A is collinear with K and L, rectangle BDLK must be twice in area to triangle ABD, since it shares a height with BK and a base with BD and a triangle's area is half the product of it's base and height.

- Since C is collinear with A and G, square BAGF must be twice in area to triangle FBC.

- Therefore rectangle BDLK must have the same area as square BAGF = AB2.

- Similarly, it can be shown that rectangle CKLE must have the same area as square ACIH = AC2.

- Adding these two results, AB2 + AC2 = BD × BK + KL × KC

- Since BD = KL, BD* BK + KL × KC = BD(BK + KC) = BD × BC

- Therefore AB2 + AC2 = BC2, since CBDE is a square.

This proof, which appears in Euclid's Elements as that of Proposition 47 in Book 1,[14] demonstrates that the area of the square on the hypotenuse is the sum of the areas of the other two squares.[15] It is therefore an areal proof in the sense of Dantzig, one that depends on areas, not lengths. This makes it quite distinct from the proof by similarity of triangles, which is conjectured to be the proof that Pythagoras used.[11][16]

Similarity proof

Using the first diagram in Euclid's proof above, three triangles can be identified, all similar figures. Each triangle has a square on its hypotenuse. Since the large triangle is made of the two smaller triangles, its area is the sum of areas of the two smaller ones. By similarity, the three squares are in the same proportions relative to each other as the three triangles, and so likewise the area of the larger square is the sum of the areas of the two smaller squares.

Proof by rearrangement

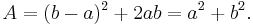

In the animation at the left, the total area and the areas of the triangles are all constant. Therefore, the total black area is constant. But the original black area of side c can be divided into two squares delineated by the triangle sides a, b, demonstrating that a2 + b2 = c2.

Another proof by rearrangement is given by the animation at the right. An initial large square is formed of area c2 by adjoining four identical right triangles, leaving a small square in the center of the big square to accommodate the difference in lengths of the sides of the triangles. Two rectangles are formed of sides a and b by moving the triangles. By incorporating the center small square with one of these rectangles, the two rectangles are made into two squares of areas a2 and b2, showing that c2 = a2 + b2.

A third graphic illustration of the Pythagorean theorem (in shades of green and blue to the right) fits parts of the sides' squares into the hypotenuse's square. This example is one of many complex geometric proofs described by Loomis.[18] The corresponding blue– and green–shaded areas are equal. Because the sum of equals are equal, the large bottom square composed of its blue and green pieces has the same area as the sum of the upper two squares made up of the same pieces. A complete proof would describe how the various parts are generated, and show that the repositioned parts fit into and fill the lower square. A Java applet on line shows how to cut the small square in more and more slices as the corresponding side gets smaller and smaller.[19]

Algebraic proof

An algebraic proof is provided by the following reasoning. A point is marked on each side of the outer square, dividing each side into two segments of lengths a and b. As shown in the illustration, the result is a large square with identical right triangles in its corners. Each pair of triangles from opposite corners forms a rectangle with area ab, so the area of all four triangles is:

- Area of 4 triangles = 2ab.

The center figure has equal sides because all the four triangles forming its border are the same. However, it might be any kind of rhombus. Next, the center figure is shown to be a square: The a-side angle and b-side angle of each of these triangles are complementary angles, that is, they sum to a right angle. However, the corner angle c of the inner figure and the two side-angles a and b sum to a straight angle. So each of the angles of the blue area in the middle is a right angle, making this area a square with side length c. The area of this square is c2. Thus the area of everything together is given by:

- Area of complete figure = c2 + 2ab.

However, as the large square has sides of length a + b, we can also calculate its area as:

- Area of complete figure = (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2.

Equating the two expressions for the total area, the result is:

A term of 2ab can be subtracted from both sides of the equation, leaving:

which is Pythagoras' theorem.

Proof by subtraction

In a rearrangement version of this proof, the figure shows two identical large squares of side a + b. The left square contains the square on the hypotenuse plus identical right triangles in its four corners. On the right, the same large square holds the squares on the other two sides plus the same four right triangles, now moved to form two rectangles of sides a and b in the bottom corners. From both identical large squares, the area of the same four right triangles of sides a, b, c is subtracted (colored). Subtracting the triangles removes the same (colored) area from the equal-area large squares, so the remaining white areas, c2 and a2 + b2, are equal.

Proof by rotation

A related algebraic proof considers rotation of a square.[20] The amount the square is rotated is described by the right triangles in the top panel. By the fourfold symmetry of the square, all four right triangles are identical. The area of the top figure is the sum of the areas of four triangles (2ab) and the area of the center square (b−a)2 so:

Rotation of the square does not change its area, and from the bottom panel this area is A = c2. Hence,

Proof using differentials

One can arrive at the Pythagorean theorem by studying how changes in a side produce a change in the hypotenuse and employing a little calculus.[21][22] This proof is a metric proof in the sense of Dantzig, as it uses lengths, not areas.

In the figure, triangle PBC is the original right triangle and triangle ABC is the modification of PBC when side PB is extended by increasing a to a + Δa. The circular arcs have radii c and c + Δc where Δc is the change in hypotenuse c that occurs as a result of the change Δa in side a.

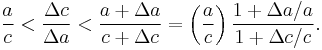

[21]

[21]The figure shows two constructions, right triangles ADP and AQP, in the upper and lower panels which will be used to find respectively upper and lower bounds of the ratio Δc/Δa. Then the limit will be taken as Δa, Δc → 0, and the resulting expression for the derivative dc /da will be used to establish Pythagoras' theorem.

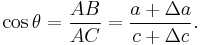

From triangle ABC (upper panel),

Construct right triangle ADP (upper panel). Then,

The last inequality results from AD > Δc , as shown in the upper panel of the figure.[23] Combining the above expressions for cos θ,

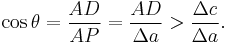

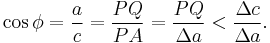

Next construct right triangle AQP (lower panel). Since both triangles AQP and PBC have an angle  ,

,

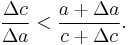

The last inequality results from PQ < Δc, as shown in the lower panel of the figure. Combining the two inequalities that were obtained using triangles ADP and AQP,

We now have upper and lower bounds for the ratio Δc /Δa. As Δa, Δc → 0, the ratio Δc /Δa becomes the derivative dc /da and the upper bound becomes the same as the lower bound a /c. Consequently,

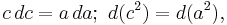

or:

which has the integral:

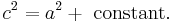

When a = 0 then c = b, so the "constant" is b2. Hence, Pythagoras' theorem is established:

Using this expression, the total differential is:

This result shows that the increase in the square of the hypotenuse is the sum of the independent contributions from the squares of the sides.

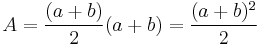

Garfield's proof

Major general James A. Garfield (later President of the United States) published a novel algebraic proof based upon equating two different determinations of the area of a trapezoid.[24][25]

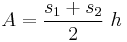

The area of a trapezoid is

where ,  and

and  are lengths of the parallel sides, and

are lengths of the parallel sides, and  is the height. The formula can be viewed as the average width of the trapezoid times the height.

is the height. The formula can be viewed as the average width of the trapezoid times the height.

Substituting for the sides and height, the area of the trapezoid in the figure is

.

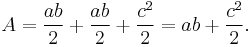

.

Identical right-angle triangles 1 and 2 each have area  , while right-angle triangle 3 has area

, while right-angle triangle 3 has area  , which happens to be half of the square on the hypotenuse of triangle 1 or triangle 2.

, which happens to be half of the square on the hypotenuse of triangle 1 or triangle 2.

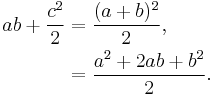

Therefore, the area of the entire trapezoid is:

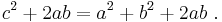

These two area determinations must be equal, so

Multiplying by 2 and rearranging:

Subtracting  from both sides, the square on the hypotenuse of either triangle 1 or triangle 2 is found to be equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides:

from both sides, the square on the hypotenuse of either triangle 1 or triangle 2 is found to be equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides:

Converse

The converse of the theorem is also true:[26]

For any three positive numbers a, b, and c such that a2 + b2 = c2, there exists a triangle with sides a, b and c, and every such triangle has a right angle between the sides of lengths a and b.

Such numbers are called a Pythagorean triple. An alternative statement is:

For any triangle with sides a, b, c, if a2 + b2 = c2, then the angle between a and b measures 90°.

This converse also appears in Euclid's Elements (Book I, Proposition 48):[27]

“If in a triangle the square on one of the sides equals the sum of the squares on the remaining two sides of the triangle, then the angle contained by the remaining two sides of the triangle is right.”

It can be proven using the law of cosines (see below under Generalizations), or by the following proof:

Let ABC be a triangle with side lengths a, b, and c, with a2 + b2 = c2. We need to prove that the angle between the a and b sides is a right angle. We construct a second triangle with sides of lengths a and b containing a right angle. By the Pythagorean theorem, it follows that the hypotenuse of this triangle has length c = √(a2 + b2), which means the hypotenuse is the same length as the first triangle. Since both triangles have the same three side lengths a, b and c, they are congruent, and so they must have the same angles. Therefore, the angle between the side of lengths a and b in our original triangle also is a right angle.

A corollary of the Pythagorean theorem's converse is a simple means of determining whether a triangle is right, obtuse, or acute, as follows. Where c is chosen to be the longest of the three sides and a + b > c (otherwise there is no triangle according to the triangle inequality). The following statements apply:[28]

- If a2 + b2 = c2, then the triangle is right.

- If a2 + b2 > c2, then the triangle is acute.

- If a2 + b2 < c2, then the triangle is obtuse.

Edsger Dijkstra has stated this proposition about acute, right, and obtuse triangles in this language:

- sgn(α + β − γ) = sgn(a2 + b2 − c2),

where α is the angle opposite to side a, β is the angle opposite to side b, γ is the angle opposite to side c, and sgn is the sign function.[29]

Consequences and uses of the theorem

Pythagorean triples

A Pythagorean triple has three positive integers a, b, and c, such that a2 + b2 = c2. In other words, a Pythagorean triple represents the lengths of the sides of a right triangle where all three sides have integer lengths.[1] Evidence from megalithic monuments on the Northern Europe shows that such triples were known before the discovery of writing. Such a triple is commonly written (a, b, c). Some well-known examples are (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13).

A primitive Pythagorean triple is one in which a, b and c are coprime (the greatest common divisor of a, b and c is 1).

The following is a list of primitive Pythagorean triples with values less than 100:

- (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (7, 24, 25), (8, 15, 17), (9, 40, 41), (11, 60, 61), (12, 35, 37), (13, 84, 85), (16, 63, 65), (20, 21, 29), (28, 45, 53), (33, 56, 65), (36, 77, 85), (39, 80, 89), (48, 55, 73), (65, 72, 97)

Incommensurable lengths

One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that line segments whose lengths are incommensurable (that is, whose ratio is an irrational number) can be constructed using a straightedge and compass. Pythagoras' theorem enables construction of incommensurable lengths because the hypotenuse of a triangle is related to the sides via the square root operation.

The figure on the right shows how to construct line segments whose lengths are in the ratio of the square root of any positive integer.[30] Each triangle has a side (labeled "1") that is the chosen unit for measurement. In each right triangle, Pythagoras' theorem establishes the length of the hypotenuse in terms of this unit. If a hypotenuse is related to the unit by the square root of a positive integer that is not a perfect square, it is a realization of a length incommensurable with the unit. Examples are √2, √3, √5 . For more detail, see Quadratic irrational.

Incommensurable lengths were contrary to a long-held belief among the Greeks. According to one legend, Hippasus of Metapontum (ca. 470 B.C.) was drowned at sea for making known the existence of the irrational or incommensurable.[31][32]

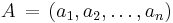

Euclidean distance in various coordinate systems

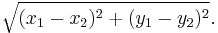

The distance formula in Cartesian coordinates is derived from the Pythagorean theorem.[33] If (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are points in the plane, then the distance between them, also called the Euclidean distance, is given by

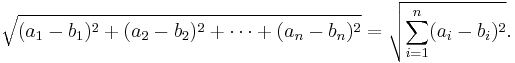

More generally, in Euclidean n-space, the Euclidean distance between two points,  and

and  , is defined, by generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, as:

, is defined, by generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, as:

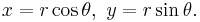

If Cartesian coordinates are not used, for example, if polar coordinates are used in two dimensions or, in more general terms, if curvilinear coordinates are used, the formulas expressing the Euclidean distance are more complicated than the Pythagorean theorem, but can be derived from it. A typical example where the straight-line distance between two points is converted to curvilinear coordinates can be found in this article. The formulas can be discovered by using Pythagoras' theorem with the equations relating the curvilinear coordinates to Cartesian coordinates. For example, the polar coordinates (r, θ) can be introduced as:

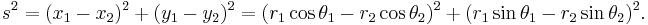

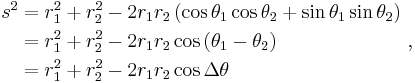

Then two points with locations (r1, θ1) and (r2, θ2) are separated by a distance s:

Performing the squares and combining terms, the Pythagorean formula for distance in Cartesian coordinates produces the separation in polar coordinates as:

using the trigonometric product-to-sum formulas. This formula is the law of cosines, sometimes called the Generalized Pythagorean Theorem.[34] From this result, for the case where the radii to the two locations are at right angles, the enclosed angle Δθ = π/2, and the form corresponding to Pythagoras' theorem is regained:  The Pythagorean theorem, valid for right triangles, therefore is a special case of the more general law of cosines, valid for arbitrary triangles.

The Pythagorean theorem, valid for right triangles, therefore is a special case of the more general law of cosines, valid for arbitrary triangles.

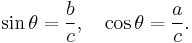

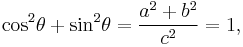

Pythagorean trigonometric identity

In a right triangle with sides a, b and hypotenuse c, trigonometry determines the sine and cosine of the angle θ between side a and the hypotenuse as:

From that it follows:

where the last step applies Pythagoras' theorem. This relation between sine and cosine sometimes is called the fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity.[35] In similar triangles, the ratios of the sides are the same regardless of the size of the triangles, and depend upon the angles. Consequently, in the figure, the triangle with hypotenuse of unit size has opposite side of size sin θ and adjacent side of size cos θ in units of the hypotenuse.

Generalizations

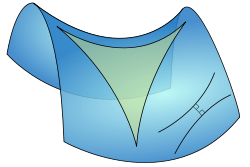

Similar figures on the three sides

green area A + B = blue area C

The Pythagorean theorem was generalized by Euclid in his Elements to extend beyond the areas of squares on the three sides to similar figures:[36]

If one erects similar figures (see Euclidean geometry) on the sides of a right triangle, then the sum of the areas of the two smaller ones equals the area of the larger one.

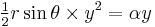

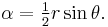

The basic idea behind this generalization is that the area of a plane figure is proportional to the product of two non-parallel lengths. One of these lengths can be taken as the side of the similar figure bordering the triangle. Another can be taken as any other side not parallel to the first. (For example, the area of a triangle with sides x and y forming angle θ is  and the proportionality factor is

and the proportionality factor is  ) When the first dimension changes, the second dimension scales with the other because the figures are similar. (That is, the ratio of the two dimensions, say r, is fixed, so in the triangle example x/y = r for all the triangles, regardless of the actual lengths, and the area is

) When the first dimension changes, the second dimension scales with the other because the figures are similar. (That is, the ratio of the two dimensions, say r, is fixed, so in the triangle example x/y = r for all the triangles, regardless of the actual lengths, and the area is  with

with  ) So the area of each figure bordering the right triangle is proportional to the square of its side bordering the right triangle. Because the sides of the right triangle are related by a2 + b2 = c2, and the areas of the figures are related to these sides by the proportionality factor, say α, the areas of the three similar figures satisfy αa2 + αb2 = αc2; that is, area of the figure on the hypotenuse is the sum of the areas of the similar figures on the other two sides.

) So the area of each figure bordering the right triangle is proportional to the square of its side bordering the right triangle. Because the sides of the right triangle are related by a2 + b2 = c2, and the areas of the figures are related to these sides by the proportionality factor, say α, the areas of the three similar figures satisfy αa2 + αb2 = αc2; that is, area of the figure on the hypotenuse is the sum of the areas of the similar figures on the other two sides.

A proof of Pythagoras' theorem can be constructed this way. For example, the starting center triangle can be replicated and used as a triangle C on its hypotenuse, and two similar right triangles (A and B ) constructed on the other two sides, formed by dividing the central triangle by its altitude. The sum of the areas of the two smaller triangles therefore is that of the third, resulting in α(a2 +b2) = α c2, or Pythagoras' theorem: (a2 +b2) = c2.

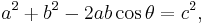

Law of cosines

The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the more general theorem relating the lengths of sides in any triangle, the law of cosines:[37]

where θ is the angle between sides a and b.

When θ is 90 degrees, then cosθ = 0, and the formula reduces to the usual Pythagorean theorem.

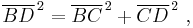

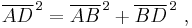

Arbitrary triangle

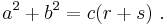

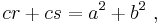

At any selected angle of a general triangle of sides a, b, c, inscribe an isosceles triangle such that the equal angles at its base θ are the same as the selected angle. Suppose the selected angle is opposite the side labeled c. A triangle ABD with angle θ opposite side a is formed with side r along c. A second triangle with angle θ opposite side b has a side with length s along c, as shown in the figure. Tâbit ibn Qorra[39] stated that the sides of the three triangles were related as:[40][41]

As the angle θ approaches π/2, the base of the isosceles triangle narrows, and lengths r and s overlap less and less. When θ = π/2, ADB becomes a right triangle, r + s = c, and the original Pythagoras' theorem is regained.

One proof observes that triangle ABC has the same angles as triangle ABD, but in opposite order. (The two triangles share the angle at vertex B, both contain the angle θ, and so also have the same third angle by the triangle postulate.) Consequently, ABC is similar to the reflection of ABD, the triangle DBA in the lower panel. Taking the ratio of sides opposite and adjacent to θ,

Likewise, for the reflection of the other triangle,

Clearing fractions and adding these two relations:

the required result.

General triangles using parallelograms

green area = blue area

A further generalization applies to triangles that are not right triangles, using parallelograms on the three sides in place of squares.[42] (Squares are a special case, of course.) The upper figure shows that for a scalene triangle, the area of the parallelogram on the longest side is the sum of the areas of the parallelograms on the other two sides, provided the parallelogram on the long side is constructed as indicated (the dimensions labeled with arrows are the same, and determine the sides of the bottom parallelogram). This replacement of squares with parallelograms bears a clear resemblance to the original Pythagoras' theorem, and was considered a generalization by Pappus of Alexandria in 4 A.D.[42]

The lower figure shows the elements of the proof. Focus on the left side of the figure. The left green parallelogram has the same area as the left, blue portion of the bottom parallelogram because both have the same base b and height h. However, the left green parallelogram also has the same area as the left green parallelogram of the upper figure, because they have the same base (the upper left side of the triangle) and the same height normal to that side of the triangle. Repeating the argument for the right side of the figure, the bottom parallelogram has the same area as the sum of the two green parallelograms.

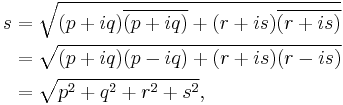

Complex arithmetic

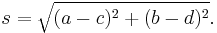

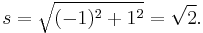

Pythagoras' formula is used to find the distance between two points in the Cartesian coordinate plane, and is valid if all coordinates are real: the distance s between the points (a, b) and (c, d) is

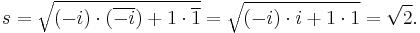

No problem arises with the formula if complex numbers are treated as vectors with real components as in x + i y = (x, y). For example, the distance s between 0 + 1i and 1 + 0i becomes the magnitude of the vector (0, 1) − (1, 0) = (−1, 1), or

However, a modification of the Pythagorean formula is necessary for a direct treatment of vectors with complex coordinates. The distance between the points with complex coordinates (a, b) and (c, d); a, b, c, and d all complex; is formulated using absolute values. The distance s is based upon the vector difference (a − c, b − d) in the following manner:[43] Let the difference a − c = p + i q, where p is the real part of the difference, q is the imaginary part and i = √(−1). Likewise, let b − d = r + is. Then:

where  is the complex conjugate of

is the complex conjugate of  . For example, the distance between the points (a, b) = (0, 1) and (c, d) = (i, 0) begins with the difference (a − c, b − d) = (−i, 1) and would work out as 0 if complex conjugates were not taken. Using the modified formula, the result is

. For example, the distance between the points (a, b) = (0, 1) and (c, d) = (i, 0) begins with the difference (a − c, b − d) = (−i, 1) and would work out as 0 if complex conjugates were not taken. Using the modified formula, the result is

The norm defined by:

is a Hermitian dot product.[44]

Solid geometry

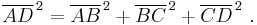

In terms of solid geometry, Pythagoras' theorem can be applied to three dimensions as follows. Consider a rectangular solid as shown in the figure. The length of diagonal BD is found from Pythagoras' theorem as:

where these three sides form a right triangle. Using horizontal diagonal BD and the vertical edge AB, the length of diagonal AD then is found by a second application of Pythagoras' theorem as:

or, doing it all in one step:

This result is the three-dimensional expression for the magnitude of a vector v (the diagonal AD) in terms of its orthogonal components {vk} (the three mutually perpendicular sides):

This one-step formulation may be viewed as a generalization of Pythagoras' theorem to higher dimensions. However, this result is really just the repeated application of the original Pythagoras' theorem to a succession of right triangles in a sequence of orthogonal planes.

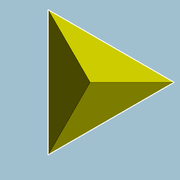

A substantial generalization of the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions is de Gua's theorem, named for Jean Paul de Gua de Malves: If a tetrahedron has a right angle corner (a corner like a cube), then the square of the area of the face opposite the right angle corner is the sum of the squares of the areas of the other three faces. This result can be generalized as in the “n-dimensional Pythagorean theorem”:[45]

Letbe orthogonal vectors in ℝn. Consider the n-dimensional simplex S with vertices

. (Think of the (n−1) dimensional simplex with vertices

not including the origin as the "hypotenuse" of S and the remaining (n−1)-dimensional faces of S as its "legs".) Then the square of the volume of the hypotenuse of S is the sum of the squares of the volumes of the n legs.

This statement is illustrated in three dimensions by the tetrahedron in the figure. The "hypotenuse" is the base of the tetrahedron at the back of the figure, and the "legs" are the three sides emanating from the vertex in the foreground. As the depth of the base from the vertex increases, the area of the "legs" increases, while that of the base is fixed. The theorem suggests that when this depth is at the value creating a right vertex, the generalization of Pythagoras' theorem applies. In a different wording:[46]

Given an n-rectangular n-dimensional simplex, the square of the (n − 1)-content of the facet opposing the right vertex will equal the sum of the squares of the (n − 1)-contents of the remaining facets.

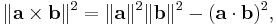

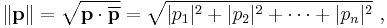

Inner product spaces

The Pythagorean theorem can be generalized to inner product spaces,[47] which are generalizations of the familiar 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional Euclidean spaces. For example, a function may be considered as a vector with infinitely many components in an inner product space, as in functional analysis.[48]

In an inner product space, the concept of perpendicularity is replaced by the concept of orthogonality: two vectors v and w are orthogonal if their inner product  is zero. The inner product is a generalization of the dot product of vectors. The dot product is called the standard inner product or the Euclidean inner product. However, other inner products are possible.[49]

is zero. The inner product is a generalization of the dot product of vectors. The dot product is called the standard inner product or the Euclidean inner product. However, other inner products are possible.[49]

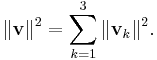

The concept of length is replaced by the concept of the norm ||v|| of a vector v, defined as:[50]

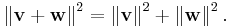

In this setting, the Pythagorean theorem states that for any two orthogonal vectors v and w of a normed inner product space,

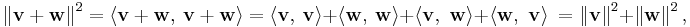

Here the vectors v and w are akin to the sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse given by the vector sum v + w. This form of the Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the properties of the inner product:

where the inner products of the cross terms are zero by orthogonality.

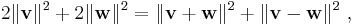

A further generalization of the Pythagorean theorem in an inner product space to non-orthogonal vectors is the parallelogram law :[50]

which says that twice the sum of the squares of the lengths of the sides of a parallelogram is the sum of the squares of the lengths of the diagonals. Any norm that satisfies this equality is ipso facto a norm corresponding to an inner product.[50]

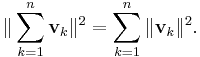

The identity can be extended to sums of more than two vectors. If v1, v2, ..., vn are pairwise-orthogonal vectors in an inner product space, application of the Pythagorean theorem to successive pairs of these vectors (as described for 3-dimensions in the section on solid geometry) results in the equation[51]

Parseval's identity is a further generalization that considers infinite sums of orthogonal vectors.

Non-Euclidean geometry

The Pythagorean theorem is derived from the axioms of Euclidean geometry, and in fact, the Pythagorean theorem given above does not hold in a non-Euclidean geometry.[52] (The Pythagorean theorem has been shown, in fact, to be equivalent to Euclid's Parallel (Fifth) Postulate.[53][54]) In other words, in non-Euclidean geometry, the relation between the sides of a triangle must necessarily take a non-Pythagorean form. For example, in spherical geometry, all three sides of the right triangle (say a, b, and c) bounding an octant of the unit sphere have length equal to π/2, which violates the Pythagorean theorem because a2 + b2 ≠ c2.

Here two cases of non-Euclidean geometry are considered — spherical geometry and hyperbolic plane geometry; in each case, as in the Euclidean case for non-right triangles, the result replacing the Pythagorean theorem follows from the appropriate law of cosines.

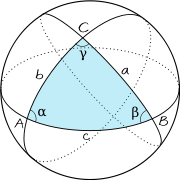

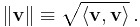

Spherical geometry

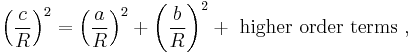

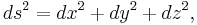

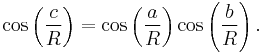

For any right triangle on a sphere of radius R (for example, if γ in the figure is a right angle), with sides a, b, c, the relation between the sides takes the form:[55]

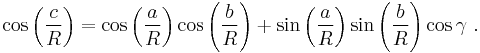

This equation can be derived as a special case of the spherical law of cosines that applies to all spherical triangles:

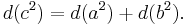

By using the Maclaurin series for the cosine function, cos x ≈ 1 − x2/2, it can be shown that as the radius R approaches infinity and the arguments a/R, b/R and c/R tend to zero, the spherical relation between the sides of a right triangle approaches the form of Pythagoras' theorem. Substituting the approximate quadratic for each of the cosines in the spherical relation for a right triangle:

Multiplying out the bracketed quantities, Pythagoras' theorem is recovered for large radii R:

where the higher order terms become negligibly small as R becomes large.

Hyperbolic geometry

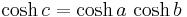

For a right triangle in hyperbolic geometry with sides a, b, c and with side c opposite a right angle, the relation between the sides takes the form: [56]

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine. This formula is a special form of the hyperbolic law of cosines that applies to all hyperbolic triangles:[57]

with γ the angle at the vertex opposite the side c.

By using the Maclaurin series for the hyperbolic cosine, cosh x ≈ 1 + x2/2, it can be shown that as a hyperbolic triangle becomes very small (that is, as a, b, and c all approach zero), the hyperbolic relation for a right triangle approaches the form of Pythagoras' theorem.

Differential geometry

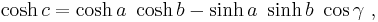

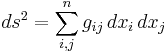

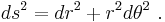

On an infinitesimal level, in three dimensional space, Pythagoras' theorem describes the distance between two infinitesimally separated points as:

with ds the element of distance and (dx, dy, dz) the components of the vector separating the two points. Such a space is called a Euclidean space. However, a generalization of this expression useful for general coordinates (not just Cartesian) and general spaces (not just Euclidean) takes the form:[58]

where gij is called the metric tensor. It may be a function of position. Such curved spaces include Riemannian geometry as a general example. This formulation also applies to a Euclidean space when using curvilinear coordinates. For example, in polar coordinates:

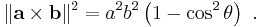

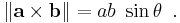

Relation to cross product

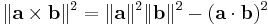

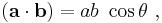

Pythagoras' theorem connects two expressions for the magnitude of the cross product.

One approach to defining a vector cross product is to require that it satisfies the equation,[59]

which involves the dot product. The right-hand side is called the Gram determinant of a and b, and represents the square of the area of the parallelogram formed by these two vectors. From this requirement along with that of orthogonality of the cross product to its constituents a and b, it follows that, apart from the trivial cases of zero and one dimensions, the cross product is defined only in three and seven dimensions.[60] Using the definition of angle in n-dimensions:[61]

this property of the cross product provides its magnitude as:

Through the fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity,[35] another form for the magnitude is found:

An alternative approach defines the cross product using this expression for its magnitude. Then reversing the above argument, the connection to the dot product:

is derived.

History

There is debate whether the Pythagorean theorem was discovered once, or many times in many places.

The history of the theorem can be divided into four parts: knowledge of Pythagorean triples, knowledge of the relationship among the sides of a right triangle, knowledge of the relationships among adjacent angles, and proofs of the theorem within some deductive system.

Megalithic monuments from circa 2500 BC in Egypt, and in Northern Europe, incorporate right triangles with integer sides.[62] Bartel Leendert van der Waerden conjectures that these Pythagorean triples were discovered algebraically by the Babylonians.[63]

Written between 2000 and 1786 BC, the Middle Kingdom Egyptian papyrus Berlin 6619 includes a problem whose solution is a Pythagorean triple.

The Mesopotamian tablet Plimpton 322, written between 1790 and 1750 BC during the reign of Hammurabi the Great, contains many entries closely related to Pythagorean triples.

In India, the Baudhayana Sulba Sutra, the dates of which are given variously as between the 8th century BC and the 2nd century BC, contains a list of Pythagorean triples discovered algebraically, a statement of the Pythagorean theorem, and a geometrical proof of the Pythagorean theorem for an isosceles right triangle. The Apastamba Sulba Sutra (circa 600 BC) contains a numerical proof of the general Pythagorean theorem, using an area computation. Van der Waerden believes that "it was certainly based on earlier traditions". According to Albert Bŭrk, this is the original proof of the theorem; he further theorizes that Pythagoras visited Arakonam, India, and copied it. Boyer (1991) thinks the elements found in the Śulba-sũtram may be of Mesopotamian derivation.[64]

With contents known much earlier, but in surviving texts dating from roughly the first century BC, the Chinese text Zhou Bi Suan Jing (周髀算经), (The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven) gives an argument for the Pythagorean theorem for the (3, 4, 5) triangle — in China it is called the "Gougu Theorem" (勾股定理).[65][66] During the Han Dynasty, from 202 BC to 220 AD, Pythagorean triples appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art,[67] together with a mention of right triangles.[68] Some believe the theorem arose first in China[69] (where it is alternately known as the "Shang Gao Theorem" (商高定理),[70] named after the Duke of Zhou's astrologer, and described in the mathematical collection Zhou Bi Suan Jing[71])

Pythagoras, whose dates are commonly given as 569–475 BC, used algebraic methods to construct Pythagorean triples, according to Proklos's commentary on Euclid. Proklos, however, wrote between 410 and 485 AD. According to Sir Thomas L. Heath, no specific attribution of the theorem to Pythagoras exists in the surviving Greek literature from the five centuries after Pythagoras lived.[72] However, when authors such as Plutarch and Cicero attributed the theorem to Pythagoras, they did so in a way which suggests that the attribution was widely known and undoubted.[6][73] “Whether this formula is rightly attributed to Pythagoras personally, [...] one can safely assume that it belongs to the very oldest period of Pythagorean mathematics.”[32]

Around 400 BC, according to Proklos, Plato gave a method for finding Pythagorean triples that combined algebra and geometry. Circa 300 BC, in Euclid's Elements, the oldest extant axiomatic proof of the theorem is presented.[74]

Pop references to the Pythagorean theorem

The Pythagorean theorem has arisen in popular culture in a variety of ways.

- A verse of the Major-General's Song in the Gilbert and Sullivan musical The Pirates of Penzance, "About binomial theorem I'm teeming with a lot o' news, With many cheerful facts about the square of the hypotenuse", with oblique reference to the theorem.

- The Scarecrow of The Wizard of Oz makes a more specific reference to the theorem when he receives his diploma from the Wizard. He immediately exhibits his "knowledge" by reciting a mangled and incorrect version of the theorem: "The sum of the square roots of any two sides of an isosceles triangle is equal to the square root of the remaining side. Oh, joy! Oh, rapture! I've got a brain!" The "knowledge" exhibited by the Scarecrow is incorrect. The accurate statement would have been "The sum of the squares of the legs of a right triangle is equal to the square of the remaining side."[75]

- In an episode of The Simpsons, after finding a pair of Henry Kissinger's glasses in a toilet at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, Homer puts them on and quotes Oz Scarecrow's mangled version of the formula. A man in a nearby toilet stall then yells out "That's a right triangle, you idiot!" (The comment about square roots remained uncorrected.)

- The Text to Speech software in Mac OS X has a voice called Ralph that recites the theorem as its example speech.

- In Freemasonry, one symbol for a Past Master is the diagram from the 47th Proposition of Euclid, used in Euclid's proof of the Pythagorean theorem.

- In 2000, Uganda released a coin with the shape of an isosceles right triangle. The coin's tail has an image of Pythagoras and the equation α2 + β2 = γ2, accompanied with the mention "Pythagoras Millennium".[76] Greece, Japan, San Marino, Sierra Leone, and Suriname have issued postage stamps depicting Pythagoras and the Pythagorean theorem.[77]

- In Neal Stephenson's speculative fiction Anathem, the Pythagorean theorem is referred to as 'the Adrakhonic theorem'. A geometric proof of the theorem is displayed on the side of an alien ship to demonstrate their understanding of mathematics.

- In Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters, the Pythagorean Theorem is shown on the corner of the blackboard as Master Shake tries to teach Meatwad about sexual education. The theorem, however, is represented incorrectly in two ways. The algebraic steps shown use different numbers than the picture indicates for the problem. Even if the numbers are changed to reflect the given picture, the solver tried to solve for the hypotenuse of the triangle, which was already given.

See also

- Pythagorean triple

- Pythagorean trigonometric identity

- Dulcarnon

- Fermat's Last Theorem

- Kātyāyana

- Linear algebra

- List of triangle topics

- Lp space

- Nonhypotenuse number

- Parallelogram law

- Rational trigonometry#Pythagoras' theorem

- Synthetic geometry

- Triangle

- Pythagorean expectation

- Ptolemy's theorem

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Judith D. Sally, Paul Sally (2007). "Chapter 3: Pythagorean triples". Roots to research: a vertical development of mathematical problems. American Mathematical Society Bookstore. p. 63. ISBN 0821844032. http://books.google.com/books?id=nHxBw-WlECUC&pg=PA63.

- ↑ Tobias Dantzig (1955). The bequest of the Greeks. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 97. http://books.google.com/?id=nSg4AAAAMAAJ&cd=1&dq=bibliogroup%3A%22Mathematics+in+retrospect%22&q=not+as+a+metric#search_anchor.

- ↑ (Maor 2007, p. 39)

- ↑ GJ Allman (1888). Thomas Spencer Baynes. ed. The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 20 (9th ed.). H.G. Allen. p. 142. http://books.google.com/books?id=C84MAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA142.

- ↑ George Johnston Allman (1889). Greek Geometry from Thales to Euclid (Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing LLC 2005 ed.). Hodges, Figgis, & Co. p. 26. ISBN 143260662X. http://books.google.com/?id=-gYCAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA26. "The discovery of the law of three squares, commonly called the "theorem of Pythagoras" is attributed to him by – amongst others –Vitruvius, Diogenes Laertius, Proclus, and Plutarch ..."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (Heath 1921, Vol I, p. 144)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Otto Neugebauer (1969). The exact sciences in antiquity (Republication of 1957 Brown University Press 2nd ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 36. ISBN 0486223329. http://books.google.com/?id=JVhTtVA2zr8C&pg=PA36.. For a different view, see Dick Teresi (2003). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science. Simon and Schuster. p. 52. ISBN 074324379X. http://books.google.com/?id=pheL_ubbXD0C&pg=PA52., where the speculation is made that the first column of a tablet 322 in the Plimpton collection supports a Babylonian knowledge of some elements of trigonometry. That notion is pretty much laid to rest by Eleanor Robson (2002). "Words and Pictures: New Light on Plimpton 322". The American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 109 (2): 105–120. doi:10.2307/2695324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2695324. See also pdf file. The accepted view today is that the Babylonians had no awareness of trigonometric functions. See Abdulrahman A. Abdulaziz (2010). "The Plimpton 322 Tablet and the Babylonian Method of Generating Pythagorean Triples". ArXiv preprint. http://arxiv.org/abs/1004.0025v1. §2, page 7.

- ↑ Mario Livio (2003). The golden ratio: the story of phi, the world's most astonishing number. Random House, Inc. p. 25. ISBN 0767908163. http://books.google.com/?id=bUARfgWRH14C&pg=PA25.

- ↑ (Loomis 1968)

- ↑ (Maor 2007, p. 39) page 39

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Stephen W. Hawking (2005). God created the integers: the mathematical breakthroughs that changed history. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 0762419229. http://books.google.com/?id=3zdFSOS3f4AC&pg=PA12.

- ↑ See for example Mike May S.J., Pythagorean theorem by shear mapping, Saint Louis University website Java applet

- ↑ Jan Gullberg (1997). Mathematics: from the birth of numbers. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 435. ISBN 039304002X. http://books.google.com/books?id=E09fBi9StpQC&pg=PA435.

- ↑ Elements 1.47 by Euclid. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 47: web page version using Java applets from Euclid's Elements by Prof. David E. Joyce, Clark University

- ↑ The proof by Pythagoras probably was not a general one, as the theory of proportions was developed only two centuries after Pythagoras; see (Maor 2007, p. 25) page 25

- ↑ Alexander Bogomolny. "Pythagorean Theorem, proof number 10". Cut the Knot. http://www.cut-the-knot.org/pythagoras/index.shtml#10. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ↑ (Loomis 1968, Geometric proof 22 and Figure 123, page= 113)

- ↑ Pythagorean Theorem: Subtle Dangers of Visual Proof by Alexander Bogomolny. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Alexander Bogomolny. "Cut-the-knot.org: Pythagorean theorem and its many proofs, Proof #3". Cut the Knot. http://www.cut-the-knot.org/pythagoras/index.shtml#3. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mike Staring (1996). "The Pythagorean proposition: A proof by means of calculus". Mathematics Magazine (Mathematical Association of America) 69 (February): 45–46. doi:10.2307/2691395. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2691395.

(An abbreviated version of the proof in this article is in the second half of Proof #40 at Bogomolny, Alexander. "Pythagorean Theorem". Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles. Alexander Bogomolny. http://www.cut-the-knot.org/pythagoras. Retrieved 2010-05-09. Archived version May 8, 2010.) - ↑ Proof #40 also summarizes a differential proof by Michael Hardy: "Pythagoras Made Difficult". Mathematical Intelligencer, 10 (3), p. 31, 1988. Although not listed in this journal's table of contents and without a doi, this article can be found at the end of the unrelated article by Bruce C. Berndt (1988). "Ramanujan—100 years old (fashioned) or 100 years new (fangled)?". The Mathematical Intelligencer 10: 24. doi:10.1007/BF03026638.

- ↑ From the figure, it is evident that point D lies inside the circle of radius c, which is why AD is larger than Δc. That fact is rigorously established by noting side CD of right triangle CDP must be less than c because it is necessarily less than the hypotenuse CP of CDP. Consequently, point D definitely is inside the circle of radius c. Similarly, point Q must lie inside the circle of radius c + Δc because CQ must be less than the hypotenuse CA of right triangle CQA, of length c + Δc. The theorem that the hypotenuse of a right triangle is longer than either of its sides does not require Pythagoras' theorem, so the derivation is not simply circular. However, it does require the triangle postulate, equivalent to Euclid's postulate of parallel lines.

- ↑ Published in a weekly mathematics column: James A Garfield (1876). The New England Journal of Education 3: 161. as noted in William Dunham (1997). The mathematical universe: An alphabetical journey through the great proofs, problems, and personalities. Wiley. p. 96. ISBN 0471176613. http://books.google.com/?id=3tG_FRQ9N1QC&cd=1&dq=%22mathematical+universe%22+inauthor%3AWilliam+inauthor%3ADunham&q=New+England+Journal#search_anchor. and in A calendar of mathematical dates: April 1, 1876 by V. Frederick Rickey

- ↑ Prof. David Lantz' animation from his web site of animated proofs

- ↑ Judith D. Sally, Paul Sally (2007-12-21). "Theorem 2.4 (Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem).". Cited work. p. 62. ISBN 0821844032. http://books.google.com/books?id=nHxBw-WlECUC&pg=PA54.

- ↑ Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 48 From D.E. Joyce's web page at Clark University

- ↑ Ernest Julius Wilczynski, Herbert Ellsworth Slaught (1914). "Theorem 1 and Theorem 2". Plane trigonometry and applications. Allyn and Bacon. p. 85. http://books.google.com/?id=vxk3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA85.

- ↑ "Dijkstra's generalization" (PDF). http://www.cs.utexas.edu/users/EWD/ewd09xx/EWD975.PDF.

- ↑ Henry Law (1853). "Corollary 5 of Proposition XLVII, Pythagoras' Theorem". The elements of Euclid: with many additional propositions, & explanatory notes to which is prefixed an introductory essay on logic. John Weale. p. 49. http://books.google.com/?id=Ssb_OnVOGLgC&pg=PA49.

- ↑ (Heath 1921, Vol I, pp. 65); Hippasus was on a voyage at the time, and his fellows cast him overboard. See James R. Choike (1980). "The pentagram and the discovery of an irrational number". The College Mathematics Journal 11: 312–316.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 A careful discussion of Hippasus' contributions is found in Kurt Von Fritz (Apr., 1945). "The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum". The Annals of Mathematics, Second Series (Annals of Mathematics) 46 (No. 2): 242–264. http://www.jstor.org/pss/1969021.

- ↑ Jon Orwant, Jarkko Hietaniemi, John Macdonald (1999). "Euclidean distance". Mastering algorithms with Perl. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 426. ISBN 1565923987. http://books.google.com/books?id=z9xMfXGoWd0C&pg=PA426.

- ↑ Wentworth, George (2009). Plane Trigonometry and Tables. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 116. ISBN 1-103-07998-0. http://books.google.com/?id=Z-O57gUYmIgC, Exercises, page 116

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Lawrence S. Leff (2005). PreCalculus the Easy Way (7th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 296. ISBN 0764128922. http://books.google.com/?id=y_7yrqrHTb4C&pg=PA296.

- ↑ Euclid's Elements: Book VI, Proposition VI 31: “In right-angled triangles the figure on the side subtending the right angle is equal to the similar and similarly described figures on the sides containing the right angle.”

- ↑ Lawrence S. Leff (2005-05-01). cited work. Barron's Educational Series. p. 326. ISBN 0764128922. http://books.google.com/?id=y_7yrqrHTb4C&pg=PA326.

- ↑ Howard Whitley Eves (1983). "§4.8:...generalization of Pythagorean theorem". Great moments in mathematics (before 1650). Mathematical Association of America. p. 41. ISBN 0883853108. http://books.google.com/books?id=9_w5jDPTvCQC&pg=PA41.

- ↑ Tâbit ibn Qorra (full name Thābit ibn Qurra ibn Marwan Al-Ṣābiʾ al-Ḥarrānī) ( 826-901 AD) was a physician living in Baghdad who wrote extensively on Euclid's Elements and other mathematical subjects.

- ↑ Aydin Sayili (Mar. 1960). "Thâbit ibn Qurra's Generalization of the Pythagorean Theorem". Isis 51 (1): 35–37. doi:10.1086/348837. http://www.jstor.org/stable/227603.

- ↑ Judith D. Sally, Paul Sally (2007-12-21). "Exercise 2.10 (ii)". Cited work. p. 62. ISBN 0821844032. http://books.google.com/books?id=nHxBw-WlECUC&pg=PA62.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 For the details of such a construction, see George Jennings (1997). "Figure 1.32: The generalized Pythagorean theorem". Modern geometry with applications: with 150 figures (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 23. ISBN 038794222X. http://books.google.com/?id=6OhcE7YQY8QC&pg=PA23.

- ↑ Arlen Brown, Carl M. Pearcy (1995). "Item C: Norm for an arbitrary n-tuple ...". An introduction to analysis. Springer. p. 124. ISBN 0387943692. http://books.google.com/books?id=Y2Mwck8Q9A4C&pg=PA124. See also pages 47-50.

- ↑ Alfred Gray, Elsa Abbena, Simon Salamon (2006). Modern differential geometry of curves and surfaces with Mathematica (3rd ed.). CRC Press. p. 194. ISBN 1584884487. http://books.google.com/?id=TGw98Z6Cv-EC&pg=PA194.

- ↑ Rajendra Bhatia (1997). Matrix analysis. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 0387948465. http://books.google.com/?id=eay3HALl620C&pg=PA21.

- ↑ For an extended discussion of this generalization, see, for example, Willie W. Wong 2002, A generalized n-dimensional Pythagorean theorem.

- ↑ Ferdinand van der Heijden, Dick de Ridder (2004). Classification, parameter estimation, and state estimation. Wiley. p. 357. ISBN 0470090138. http://books.google.com/books?id=krSB9PIKMSYC&pg=PA357.

- ↑ Qun Lin, Jiafu Lin (2006). Finite element methods: accuracy and improvement. Elsevier. p. 23. ISBN 7030166566. http://books.google.com/books?id=cMvAqzMuAWgC&pg=PA23.

- ↑ Howard Anton, Chris Rorres (2010). Elementary Linear Algebra: Applications Version (10th ed.). Wiley. p. 336. ISBN 0470432055. http://books.google.com/books?id=1PJ-WHepeBsC&pg=PA336.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Karen Saxe (2002). "Theorem 1.2". Beginning functional analysis. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 0387952241. http://books.google.com/books?id=QALoZC64ea0C&pg=PA7.

- ↑ Douglas, Ronald G. (1998). Banach Algebra Techniques in Operator Theory, 2nd edition. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. pp. 60–1. ISBN 978-0387983776. http://books.google.com/?id=-OdfXeNmrT0C&pg=PA60#v=onepage&q.

- ↑ Stephen W. Hawking. cited work. p. 4. ISBN 0762419229. http://books.google.com/books?id=3zdFSOS3f4AC&pg=PA4.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein (2003). CRC concise encyclopedia of mathematics (2nd ed.). p. 2147. ISBN 1584883472. http://books.google.com/books?id=aFDWuZZslUUC&pg=PA2147. "The parallel postulate is equivalent to the Equidistance postulate, Playfair axiom, Proclus axiom, the Triangle postulate and the Pythagorean theorem."

- ↑ Alexander R. Pruss (2006). The principle of sufficient reason: a reassessment. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 052185959X. http://books.google.com/books?id=8qAxk1rXIjQC&pg=PA11. "We could include...the parallel postulate and derive the Pythagorean theorem. Or we could instead make the Pythagorean theorem among the other axioms and derive the parallel postulate."

- ↑ Barrett O'Neill (2006). "Exercise 4". Elementary differential geometry (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 441. ISBN 0120887355. http://books.google.com/?id=OtbNXAIve_AC&pg=PA441.

- ↑ Saul Stahl (1993). "Theorem 8.3". The Poincaré half-plane: a gateway to modern geometry. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 122. ISBN 086720298X. http://books.google.com/?id=TABicHVMQhMC&pg=PA122.

- ↑ Jane Gilman (1995). "Hyperbolic triangles". Two-generator discrete subgroups of PSL(2,R). American Mathematical Society Bookstore. ISBN 0821803611. http://books.google.com/?id=YRFz9Zj_vAAC&pg=PA74.

- ↑ Tai L. Chow (2000). Mathematical methods for physicists: a concise introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0521655447. http://books.google.com/?id=MpRXPOYZzfUC&pg=PA52.

- ↑ WS Massey (Dec. 1983). "Cross products of vectors in higher dimensional Euclidean spaces". The American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 90 (10): 697–701. doi:10.2307/2323537. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2323537.

- ↑ Although a cross-product involving n−1 vectors can be found in n-dimensions, a cross-product involving only two vectors can be found only in 3-dimensions and in 7-dimensions. See Pertti Lounesto (2001). "§7.4 Cross product of two vectors". Clifford algebras and spinors (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0521005515. http://books.google.com/?id=kOsybQWDK4oC&pg=PA96.

- ↑ Francis Begnaud Hildebrand (1992). Methods of applied mathematics (Reprint of Prentice-Hall 1965 2nd ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 24. ISBN 0486670023. http://books.google.com/?id=17EZkWPz_eQC&pg=PA24.

- ↑ "Megalithic Monuments.". http://hyperion.cc.uregina.ca/~astro/Mega_circ.html.

- ↑ (van_der_Waerden 1983, p. 5) See also Frank Swetz, T. I. Kao (1977). Was Pythagoras Chinese?: An examination of right triangle theory in ancient China. Penn State Press. p. 12. ISBN 0271012382. http://books.google.com/?id=WaaGNz9G7l8C&pg=PA12&dq=%22Babylonian+tables+of+number+triples%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=%22Babylonian%20tables%20of%20number%20triples%22.

- ↑ Carl Benjamin Boyer (1968). "China and India". A history of mathematics. Wiley. p. 229. http://books.google.com/?id=1ZDuAAAAMAAJ&cd=1&dq=China+and+India+rules+for+the+construction+of+right+angles+inauthor%3ACarl+inauthor%3ABenjamin+inauthor%3ABoyer&q=diagonal+of+a+rectangle+is+equal+to+the+sum+#search_anchor. "we find rules for the construction of right angles by means of triples of cords the lengths of which form Pythagorean triages, such as 3, 4, and 5, or 5, 12, and 13, or 8, 15, and 17, or 12, 35, and 37. However all of these triads are easily derived from the old Babylonian rule; hence, Mesopotamian influence in the Sulvasũtras is not unlikely. Aspastamba knew that the square on the diagonal of a rectangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the two adjacent sides, but this form of the Pythagorean theorem also may have been derived from Mesopotamia. [...] So conjectural are the origin and period of the Sulvasũtras that we cannot tell whether or not the rules are related to early Egyptian surveying or to the later Greek problem of altar doubling. They are variously dated within an interval of almost a thousand years stretching from the eighth century B.C. to the second century of our era."; See also Carl B. Boyer , Uta C. Merzbach (2010). A History of Mathematics (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0470525487. http://books.google.com/?id=xwIZQwAACAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=editions:UOM39015015720447.

- ↑ Robert P. Crease (2008). The great equations: breakthroughs in science from Pythagoras to Heisenberg. W W Norton & Co.. p. 25. ISBN 039306204X.

- ↑ A rather extensive discussion of the origins of the various texts in the Zhou Bi is provided by Christopher Cullen (2007). Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China: The 'Zhou Bi Suan Jing'. Cambridge University Press. pp. 139 f. ISBN 0521035376. http://books.google.com/?id=U9E88abLP10C&pg=PA139&dq=to+datable++events+%22relate+the+material%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=to%20datable%20%20events%20%22relate%20the%20material%22.

- ↑ This work is a compilation of 246 problems, some of which survived the book burning of 213 BC, and was put in final form before 100 AD. It was extensively commented upon by Liu Hui in 263 AD. Philip D Straffin, Jr. (2004). "Liu Hui and the first golden age of Chinese mathematics". In Marlow Anderson, Victor J. Katz, Robin J. Wilson. Sherlock Holmes in Babylon: and other tales of mathematical history. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 69 ff. ISBN 0883855461. http://books.google.com/books?id=BKRE5AjRM3AC&pg=PA69. See particularly §3: Nine chapters on the mathematical art, pps. 71 ff.

- ↑ Kangshen Shen, John N. Crossley, Anthony Wah-Cheung Lun (1999). The nine chapters on the mathematical art: companion and commentary. Oxford University Press. p. 488. ISBN 0198539363. http://books.google.com/?id=eiTJHRGTG6YC&pg=PA488.

- ↑ In particular, Li Jimin; see Centaurus, Volume 39. Copenhagen: Munksgaard. 1997. pp. 193 & 205. http://books.google.com/?id=UJlFAAAAYAAJ&q=%22Shang+Gao+Theorem%22&dq=%22Shang+Gao+Theorem%22&cd=2.

- ↑ Chen, Cheng-Yih (1996). "§3.3.4 Chén Zǐ's formula and the Chóng-Chã method; Figure 40". Early Chinese work in natural science: a re-examination of the physics of motion, acoustics, astronomy and scientific thoughts. Hong Kong University Press. p. 142. ISBN 962209385X. http://books.google.com/?id=2Wxj0SW9hBgC&pg=PA139.

- ↑ Wen-tsün Wu (2008). "The Gougu theorem". Selected works of Wen-tsün Wu. World Scientific. p. 158. ISBN 9812791078. http://books.google.com/?id=xV4lECaKDzwC&pg=PA158.

- ↑ (Euclid 1956, p. 351) page 351

- ↑ An extensive discussion of the historical evidence is provided in (Euclid 1956, p. 351) page=351

- ↑ Asger Aaboe (1997). Episodes from the early history of mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 51. ISBN 0883856131. http://books.google.com/books?id=5wGzF0wPFYgC&pg=PA51. "...it is not until Euclid that we find a logical sequence of general theorems with proper proofs."

- ↑ "The Scarecrow's Formula". Internet Movie Data Base. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032138/quotes?qt0409923. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ "Le Saviez-vous ?". http://homepage.sefanet.ch/meylan-sa/saviez-vous1.htm.

- ↑ Miller, Jeff (2007-08-03). "Images of Mathematicians on Postage Stamps". http://jeff560.tripod.com/stamps.html. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

References

- Bell, John L. (1999). The Art of the Intelligible: An Elementary Survey of Mathematics in its Conceptual Development. Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-5972-0. http://publish.uwo.ca/~jbell/

- Euclid (1956). Translated by Johan Ludvig Heiberg with an introduction and commentary by Sir Thomas L. Heath. ed. The Elements (3 vols.). Vol. 1 (Books I and II) (Reprint of 1908 ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-60088-2 On-line text at Euclid

- Heath, Sir Thomas (1921). "The ‘Theorem of Pythagoras’". A History of Greek Mathematics (2 Vols.) (Dover Publications, Inc. (1981) ed.). Clarendon Press, Oxford. p. 144 ff. ISBN 0-486-24073-8. http://books.google.com/?id=h4JsAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA144.

- Libeskind, Shlomo (2008). Euclidean and transformational geometry: a deductive inquiry. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 0763743666. http://books.google.com/books?id=6YUUeO-RjU0C&pg=PA41. This high-school geometry text covers many of the topics in this WP article.

- Loomis, Elisha Scott (1968). The Pythagorean proposition (2nd ed.). The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. ISBN 978-0873530361 For full text of 2nd edition of 1940, see Elisha Scott Loomis. "The Pythagorean proposition: its demonstrations analyzed and classified, and bibliography of sources for data of the four kinds of proofs". Education Resources Information Center. Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the U.S. Department of Education. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/32/54/86.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-04. Originally published in 1940 and reprinted in 1968 by National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, isbn=0873530365.

- Maor, Eli (2007). The Pythagorean Theorem: A 4,000-Year History. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12526-8. http://books.google.com/?id=Z5VoBGy3AoAC&printsec=frontcover&q

- Stillwell, John (1989). Mathematics and Its History. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96981-0 Also ISBN 3-540-96981-0.

- Swetz, Frank; Kao, T. I. (1977). Was Pythagoras Chinese?: An Examination of Right Triangle Theory in Ancient China. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0271012382

- van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert (1983). Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations. Springer. ISBN 3540121595. http://books.google.com/?id=_vPuAAAAMAAJ&q=%22Pythagorean+triples%22++%22Babylonian+scribes%22+inauthor:van+inauthor:der+inauthor:Waerden&dq=%22Pythagorean+triples%22++%22Babylonian+scribes%22+inauthor:van+inauthor:der+inauthor:Waerden&cd=1

External links

- Pythagorean Theorem (more than 70 proofs from cut-the-knot)

- Interactive links:

- Interactive proof in Java of The Pythagorean Theorem

- Another interactive proof in Java of The Pythagorean Theorem

- Pythagorean theorem with interactive animation

- Animated, Non-Algebraic, and User-Paced Pythagorean Theorem

- Pythagorean Theorem and Right triangle formulas

- History topic: Pythagoras's theorem in Babylonian mathematics

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Pythagorean theorem" from MathWorld.

- Euclid (David E. Joyce, ed. 1997) [c. 300 BC]. Elements. http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/java/elements/toc.html. Retrieved 2006-08-30. In HTML with Java-based interactive figures.

![1-\left(\frac{c}{R}\right)^2= \left[1-\left(\frac{a}{R}\right)^2 \right]\left[1-\left(\frac{b}{R}\right)^2 \right] + \ \mathrm{higher\ order\ terms}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/728048e96e4f839d2e8640f3389c9b5a.png)